About the Author

STYLE is the new novel for 2015. Style Interview [More...]- Joseph Connolly entry in Who’s Who

- Book Collecting and Me

- A Book that Changed Me: Far from the Madding Crowd

- Memories of Flask Walk

Interviews

Boys and Girls Interview [More...]Independent on Sunday [More...]

Camden New Journal [More...]

Financial Times [More...]

Spectator [More...]

Daily Telegraph [More...]

The Big Issue [More...]

Metro [More...]

WHO'S WHO ENTRY

Novelist and author; b 23 March 1950; s of Joseph and Lena (nee Forte) Connolly; m 1970, Patricia Quinn; one s one d. Educ: Oratory Sch. Apprentice then Ed, Hutchinson Publishers, 1969-71; owner, Flask Bookshop, Hampstead, 1975-88; columnist, The Times, 1984-88; regular contributor, Times, Daily Telegraph and other nat. newspapers, 1984 -; occasional writer Spectator, Independent and others. Restaurant reviewer for the Hampstead & Highgate Express (Ham & High) 2009 – .Founder Mem, Useless Inf. Soc, 1994 -; Hon Life Mem, Wodehouse Soc; Soc of Authors, Royal Soc Literature, Patron of Royal Free Charity. Publications: Collecting Modern First Editions, 1977; P. G. Wodehouse: an illustrated biography, 1979; Jerome K. Jerome: a critical biography, 1981; Modern First Editions: their value to collectors, 1984, The Penguin Book Quiz Book, 1985; Children's Modern First Editions, 1988; Beside the Seaside, 1999; All Shook Up: A Flash of the Fifties, 2000; Christmas and How to Survive it, 2003; Wodehouse, 2004; Faber and Faber: Eighty Years of Book Cover Design, 2009; THE A-Z OF EATING OUT, 2014. Novels: Poor Souls, 1995; This Is It, 1996; Stuff, 1997; Summer Things, 1998 (filmed as Embrassez Qui Vous Voudrez, and, in English, as Summer Things, 2002: winner of the Monte Carlo Film Institute award for best novel adaptation); Winter Breaks, 1999: It Can't Go On, 2000; S.O.S., 2001; The Works, 2003; Love Is Strange, 2005; Jack The Lad And Bloody Mary, 2007; England's Lane 2012; Boys and Girls, 2014; Style, 2015;; contributor: Jerome K. Jerome: My Life and Times, 1992; Booker 30: a celebration of the Booker Price for Fiction 1969-1998, 1998; British Greats, 2000; The Man Booker Prize: 35 years of the best in contemporary fiction 1969-2003, 2003; British Comedy Greats, 2003; Icons in the Fire: the decline and fall of almost everybody in the British film industry 1984-2000 by. Alexander Walker (J.C is A.W's Literary Executor) 2004; Private Passions by Michael Berkeley, 2005. Introduction to Folio 60: A Bibliography Of The Folio Society 1947-2007 by Paul Nash (2007). Foreword to On The Art Of Making Up One's Mind by Jerome K. Jerome (2009). Introduction to Christmas Pudding by Nancy Mitford (2011). Recreations: books, Times crossword, wine, lunching and loafing. Address: c/o Jonathan Lloyd, Curtis Brown Group Ltd, Haymarket House, 28-29 Haymarket, London SW1Y 4SP. T: 020 7393 4400. Cb@curtisbrown.co.uk. Faber and Faber Ltd, 3 Queen Square, W8IN 3AU. T: 0207 465 0045. Official website www.josephconnolly.co.uk Clubs: Garrick, Chelsea Arts, Groucho, Club at The Ivy.

Novelist and author; b 23 March 1950; s of Joseph and Lena (nee Forte) Connolly; m 1970, Patricia Quinn; one s one d. Educ: Oratory Sch. Apprentice then Ed, Hutchinson Publishers, 1969-71; owner, Flask Bookshop, Hampstead, 1975-88; columnist, The Times, 1984-88; regular contributor, Times, Daily Telegraph and other nat. newspapers, 1984 -; occasional writer Spectator, Independent and others. Restaurant reviewer for the Hampstead & Highgate Express (Ham & High) 2009 – .Founder Mem, Useless Inf. Soc, 1994 -; Hon Life Mem, Wodehouse Soc; Soc of Authors, Royal Soc Literature, Patron of Royal Free Charity. Publications: Collecting Modern First Editions, 1977; P. G. Wodehouse: an illustrated biography, 1979; Jerome K. Jerome: a critical biography, 1981; Modern First Editions: their value to collectors, 1984, The Penguin Book Quiz Book, 1985; Children's Modern First Editions, 1988; Beside the Seaside, 1999; All Shook Up: A Flash of the Fifties, 2000; Christmas and How to Survive it, 2003; Wodehouse, 2004; Faber and Faber: Eighty Years of Book Cover Design, 2009; THE A-Z OF EATING OUT, 2014. Novels: Poor Souls, 1995; This Is It, 1996; Stuff, 1997; Summer Things, 1998 (filmed as Embrassez Qui Vous Voudrez, and, in English, as Summer Things, 2002: winner of the Monte Carlo Film Institute award for best novel adaptation); Winter Breaks, 1999: It Can't Go On, 2000; S.O.S., 2001; The Works, 2003; Love Is Strange, 2005; Jack The Lad And Bloody Mary, 2007; England's Lane 2012; Boys and Girls, 2014; Style, 2015;; contributor: Jerome K. Jerome: My Life and Times, 1992; Booker 30: a celebration of the Booker Price for Fiction 1969-1998, 1998; British Greats, 2000; The Man Booker Prize: 35 years of the best in contemporary fiction 1969-2003, 2003; British Comedy Greats, 2003; Icons in the Fire: the decline and fall of almost everybody in the British film industry 1984-2000 by. Alexander Walker (J.C is A.W's Literary Executor) 2004; Private Passions by Michael Berkeley, 2005. Introduction to Folio 60: A Bibliography Of The Folio Society 1947-2007 by Paul Nash (2007). Foreword to On The Art Of Making Up One's Mind by Jerome K. Jerome (2009). Introduction to Christmas Pudding by Nancy Mitford (2011). Recreations: books, Times crossword, wine, lunching and loafing. Address: c/o Jonathan Lloyd, Curtis Brown Group Ltd, Haymarket House, 28-29 Haymarket, London SW1Y 4SP. T: 020 7393 4400. Cb@curtisbrown.co.uk. Faber and Faber Ltd, 3 Queen Square, W8IN 3AU. T: 0207 465 0045. Official website www.josephconnolly.co.uk Clubs: Garrick, Chelsea Arts, Groucho, Club at The Ivy.

Book Collecting and Me

It was thirty years ago today, and I can hardly believe it. 1977 saw the publication of my very first book, COLLECTING MODERN FIRST EDITIONS — something of a pioneering work in those days, though nonetheless good and bad in roughly equal parts. Of course I didn't invent the collecting of first editions — this unquenchable mania has been seething from just about as long ago as the invention of printing (when the second edition of Johnson's Dictionary was published, for instance, there were those who sneeringly rejected it in favour of the far less accurate first). But in the early 1970's, when my own book collecting obsession dramatically tightened its hold on me (and I had barely left school) there seemed to be a cut-off point tacitly agreed upon between dealers and collectors that pretty much excluded any author after Greene and Waugh, Eliot and Auden. Very few novels, plays or volumes of poetry of the l950's or 1960's were deemed to be very special in any way at all from a collector's point of view, and even the key works such as Kingsley Amis's LUCKY JIM, Iris Murdoch's UNDER THE NET, Ted Hughes's THE HAWK IN THE RAIN, John Osborne's LOOK BACK IN ANGER — none of them would have fetched much more than a fiver. In 1978 I paid £8 for a mint and jacketed first edition of LORD OF THE FLIES, and the dealer was delighted to have found a mug to take it off his hands: £2000 today for such a copy would be considered a bargain.

Of course it took me a little while to quite understand that not every book that happened to be a first edition was therefore intrinsically desirable. The very first first edition I acquired was when I was seventeen and still at boarding school, from a wonderful and towering treasure house of a bookshop in Reading, of all places, which later burned to the ground (nothing to do with me). A collection of untypically mediocre poems by the giant John Masefield in a knocked-about binding (no jacket, but naturally) and the inscription on the flyleaf reading 'To my sweet little Sammy, big kiss from his Auntie Vi'. Cheap, though, at under a pound (I sold it later in my own antiquarian bookshop for twenty-five pence; it had festered on the shelves for just years and years). So always be guided by your own personal taste, keep in mind that condition is all, and do not be ashamed of your quirks and peccadilloes: if you love American hard-boiled pulp fiction or Enid Blyton, then collect them.

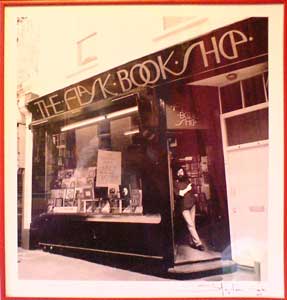

So I thought I might broaden out the interest a bit, and inject a little fun into the business. By 1975 I was myself an antiquarian and secondhand dealer — The Flask Bookshop in London's Hampstead — largely because it was a way of funding my collection. It was an immensely popular and successful shop at the time (it dwindled as Hampstead's trading identity tangibly shifted from the overtly arty and bookish to the 'upwardly mobile' and then the frankly flashy: I finally sold out in 1988). Although a great deal of good stock was delivered to my door, my wife Patricia and I would plan little day trips for most Mondays when the shop was closed (because it was very much a one-man show: I could never have afforded an assistant). We went wherever there was a good clutch of secondhand booksellers — most nice places, really: Brighton, Bath, Oxford and so on. I would take with me maybe thirty or forty pounds in cash, this to cover train fares, lunch and all the buying; we only stopped foraging for more books when the two of us could carry no more. Those Were, as they say, the days.

When my interest in very modern first editions grew (the 1950's and 1960's stuff) I knew I needed a reference work to tell me what was out there: there wasn't one. and so I wrote it. I included all sorts of surprises: Greene and Waugh were there, of course, but so were Agatha Christie, Anthony Buckeridge's JENNINGS books and also Billy Bunter. The other reason the book was different was that I wrote the intro and the entries with an enthusiasm I genuinely felt, and as much real humour as I could muster — the average book about books being noted for neither. I included anecdotes about my daily life in bookselling: that time a lugubrious fellow bought five of the novels from the eleven-volume CORRIDORS OF POWER series, highly regarded at the time. ''Well, you must really like Snow," I said to him. "I don't mind too much,'' he solemnly replied: ''it's the slush I can't stand". Then there was a young fellow who had been charged by his mother to go and buy a book, but he was damned if he could remember the title, though he felt sure it was something to do with Delius. We combed my admittedly smallish music section to no avail, and he went back home for further instruction. It turned out his mother was after THE COMPLETE COOKERY COURSE: by one Delius Miff.

All this jollity was well received, and the book was given a lot of press attention (not least in the Telegraph Magazine) possibly due to my tender years.

Godfrey Smith of The Sunday Times came to interview me in the bookshop and the bottle of Beaujolais I produced he pronounced agreeable, the second even more so; the third bottle was so agreeable as to be no more than an odious toady, but still we didn't despise it. The Flask Bookshop was always that sort of a place.

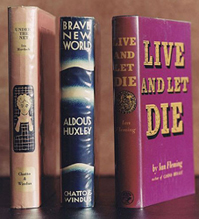

I was lucky enough to have been published by the now defunct Studio Vista — as known in those days for illustrated books as Thames & Hudson — and so there were plenty of luscious colour pictures: book porn, for those whose tastes were bent that way. In the book collecting fraternity — and it was rather brotherly, on the whole: understanding and mutually supportive at those throat-clutching moments when you just had to go out and acquire a beautiful book right now this minute — I was hardly alone in loving the Uniform Edition: the rows of books all the same format — Fleming's Bond books, maybe, or Anthony Powell's DANCE TO THE MUSIC OF TIME sequence. And of course all the modern classic authors — Woolf, Lawrence, Huxley and so on — had collected editions which often were numbered, and therefore of course you had to plot to get the lot.

Collectors of early Penguins — usually the first thousand — were similarly afflicted: the numbering of sets has always been a great way for publishers to shift a pile of books. I think I wanted to own a library of uniform sets long before I wanted even to read them (although I did read them, eventually) — and certainly before I imagined I could maybe even write a few books myself. At which point I might mention that my publisher, Faber and Faber, have just put all my novels to date into a — gasp! — uniform collected edition: my delight and cup both runneth over.

And of course my escalating keenness on collecting made me an increasingly lousy bookseller, because all of the best stuff I kept for myself. I remember once being asked to an address in Harrow — a small and humble semi — with a view to buying a small collection of first editions, because the middle-aged couple were moving to the coast and didn't want the bother of packing them up. The collection was indeed very small — maybe just 150 books — but each of them was in quite superb condition (ever more important: unless a book is inordinately rare it ls extremely difficult to find a buyer if the dust-wrapper is ruined or absent, more about which later). And there were rarities: Waugh's DECLINE AND FALL, Greene's THE MAN WITHIN, Eliot's OLD POSSUM... I was elated and yet appalled: I simply couldn't afford these, and yet I had to have them. Well the old fellow was really awfully decent — even asked me to sign what was still then my one and only book (COLLECTING MODERN FIRST EDITIONS — what else? — from which he had gleaned the values: all very ironing no doubt) — and we negotiated a lowish price, payable in three instalments. and then he offered to drive me back to Hampstead with the books (I had no car: still haven't). Despite all his generosity, though, I knew I'd make no money because the best of these were destined for my own collection: not at all professional. I asked the fellow on the way back if he wasn't sad to be parting with the books (while willing him to not go changing his mind). He cared more, he said, about having to say goodbye to his typewriters.

His garage, apparently, contained about 300 of the things, vintage, and all in perfect working order. He also asked me to spare a thought for his wife: she was getting rid of a loftful of sewing machines — about 150 in all, he reckoned — not to say every single one of her ninety-two teapots. (You've got to watch these collectors, you know — they can go a bit funny. I knew a — female, mercifully — Beatrix Potter fanatic who at all times, she assured me, wore underwear emblazoned with Jemima Puddleduck for preference, although she boasted quite a cache of smalls bearing Mrs Tiggywinkle too: I did not verify this).

Costs, of course, now are wild: I never myself spent more than £40 on a first edition. I always did, though, insist on the presence of the dust-wrapper (what collectors call the jacket) for aesthetic reasons as well as the fact that one is always after a book in a state as close as possible to the original. But nowadays if a dust-wrapper is marked or slightly torn or has its price cut from the inside flap, it is rejected or marked down hugely: absurd, to my mind.

Some dust-wrappers, though, are of legendary rarity. We are told that the bulk of wrappers for Aldous Huxley's BRAVE NEW WORLD, for instance, were destroyed in a warehouse fire, making a fine example of just the wrapper worth between ten and twenty times the value of the book. The same is true of Graham Greene's BRIGHTON ROCK — maybe £500 in its russet cloth boards, or £15 — 20,000 with its wrapper: strange, but true.

Ever escalating rents, ebay and Amazon render virtually impossible the one-horse and instinctive way I went about things — but this was the real way, the best way, as all collectors know. The smell and thrill of an old bookshop the moment you enter will never be replaced by the click of a mouse — scrolling through dozens of 'rarities', each of them instantly available.

If you have money to spare, it is still possible to collect first editions the old way visiting fine bookshops and cultivating an acquaintance with the proprietors, who are, incidentally, far more sane than you might have heard tell, and certainly a good deal less deranged, obsessive and compulsively rude than they used to be. I remember one prime example in Bell Street, London, who sat like a Buddha (though lacking the benignity) glowering amid his thousands of thoroughly unclassified books, piled up to the ceiling and obliterating the windows. He always wore a quilted coat and was generally found to be gnashing at an apple: someone told me he ate up to twenty a day, to the exclusion of all else (the reason being, the thinking went, because he liked them). You would tap on the permanently locked door and shout through the letter box that you'd like to come in. ''Why...?!'' he would bellow back. ''Um... to look at the books...?''. ''Books? Got no books. Clear out of it!". Very occasionally he would let you in, though — follow you round and — spitting through his pippin — tell you not to even think of touching a single damn thing. If you asked the price of a book, it was invariably not for sale. Another shall we say singular character I recall — eighty-five if he was a day — nursed a profound disgust for any book printed after the dawn of the eighteenth century. From the contemptible more modern books that he was sometimes obliged to buy as part of a lot he would tear out leaves at random and use them as spills to light up a ceaseless stream of noxious cigarillos.

The new breed of specialist dealer is all about efficiency, knowledge, good manners and sound business sense. And really rather expensive. There are still top rate modern first edition dealers in London — Ulysses in Museum Street, several in Cecil Court (notably Nigel Williams — not the author) and Heywood Hill in Curzon Street, among others. The quality, scarceness and condition of the stock is generally very high, and so, inevitably, are the prices. Occasionally I am offered some or other very juicy rarity at a cost that just makes me laugh out loud, quite frankly: what's the good of books if you have to remortgage the building that houses them? In Paris though, the scene is still very leisurely and old school. It is not by accident that a bookshop is called a 'librairie' — you are invited to survey a fellow enthusiast's personal collection, you are expected to admire and chatter knowledgeably and at length, rather as one might as part of a literary salon: commerce is rarely mentioned. Rue de l'Odeon in St. Germain is lined with such establishments, and a visit to the legendary English bookshop Shakespeare and Company, set so gloriously opposite Notre Dame, is obligatory: at once romantic and highly stimulating. It is charmingly and efficiently run by Sylvia Whitman, daughter of the renowned owner George and a descendent of Walt: treasures are to be found.The kick for me in book collecting — apart from the all-important thrill of the chase — lay in buying CASINO ROYALE, for instance, from Ian Fleming's secretary at The Sunday Times. Or LUCKY JIM — Kingsley Amis's presentation copy to John Braine (bought from Braine, over a drlnk)... and then ROOM AT THE TOP — John Braine's presentation copy to Kingsley Amis (bought from Amis over, as I recall, rather more than just the one). Rather strangely, both authors — who had been good friends in the sixties, and fellow members of the 'Fascist Lunch' get-togethers at Bertorelli's in Charlotte Street — independently came to live within two minutes of my bookshop (Amis in the self-same street) though to my knowledge they didn't meet again. Braine was way past his prime by then, and generally in a rather bad way; he called me Jaw (as in Jaw Lumpton). Kingsley became a bit of a chum, though. I can recall many lunches and incidents, though one of the more vivid concerns an amateur poetry competition set, think, by The Daily Mail. He and fellow judge Laurie Lee were to be paid in multiple cases of the 10 year- old Macallan malt whisky (a form of fee quite often requested) and one evening I was happy to witness the two of them on their hands and knees on the floor of Kingsley's drawing room, surrounded by a sea of papers. Their four hands clutched a single knitting needle (could have been a skewer) with which they mimicked the action of stirring a cauldron, while whooping. Then it plunged downwards and stabbed a random sheet of paper, which was immediately and solemnly pronounced to be the fitting and worthy winner of this grand competition; it was later agreed that these two eminent writers had chosen wisely — it was, London's literati concurred, a very fine poem indeed.

Thirty years on, I am happier to write and read books than to collect them. I am pleased to own one or two volumes that are accidentally valuable, though I am delighted too in having thousands more worth no more than a notional value. It was never about the money — just the pursuit of books, the pleasure they continue to give me, and all the laughs along the way.

From The Sunday Telegraph

A BOOK THAT CHANGED ME: FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD by Thomas Hardy

Well I was just seventeen — though this was not the first time had been romantically tickled and captivated by Thomas Hardy. TESS OF THE D'URBERVILLES had been an O Level set book which I had found myself loving, while not even partially understanding a good deal of the (particularly sexual) subtleties. FAR FROM THE MADDING CROWD was something rather less grand, maybe, but (what relief) with a much more straightforward allure. The title too appealed to me greatly — the quirkiness as well as the apparently rather hippy-ish sentiment (although hippies, I knew, only ever seemed to travel in a horde, in order to merge with a further mob). I was, of course, unaware that it was a quotation: I had never heard of Thomas Gray, and nor of his Elegy. I admit, though, to having been bamboozled by the passion — obsession, indeed — that Bathsheba Everdene effortlessly evoked within the big and beating breasts of Gabriel Oak and Farmer Boldwood: her dilly-dallying and reserve, and then the bouts of enthusiasm and outright flirtatiousness appeared to me to be utterly infuriating, to be perfectly frank (I did not know of the wiles of women, and nor do I now) but all became plain to me once Miss Everdene was revealed to be the divine Julie Christie in the newly-released film. It was vastly overlong, and dull in ways that Hardy could never be — but it did reinforce my opinion that Oak was worthy and sincere, but oh so plodding and predictable, while Boldwood, quite simply, was deranged (and not maybe solely as a result of Bathsheba's shenanigans). It was always clear that Troy would be the one she would go for — he was faithless, vain, terminably unreliable and not even landed: the fact that he was a handsome and dashing swordsman was more than enough (women, eh?) and in the film the further fact that he looked like a Beatle and was stitched into a scarlet tunic (Sergeant not just Troy, but Pepper too) pretty much clinched it. And it was maybe because I was wise enough to know that a schoolboy such as I had very little chance of becoming either a Beatle or the everlasting love of Julie Christie's life that I decided instead to be Thomas Hardy.

I had done this before: been driven to emulate the authors I most admired. Before I discovered Waugh and Amis, Dickens and Hardy, I had read little more than Anthony Buckeridge's JENNINGS books, all of James Bond, and a great deal of P. G. Wodehouse. So at the age of seventeen I had knocked out a 55,000-word novel about this boarding school, see, with lots of upper class and hobbles idiots with treble-barrelled names (more than one possessed of a stammer) who had to do battle with a swarthy villain, wholly bent upon conquering the planet. I called the book PARADISE MISLAID, which had no reference at all to any of the above, and it hardly needs to be said that the whole thing was terrible, utterly dire. But now I, a Londoner who knew nothing of country ways and nor of the nineteenth century, determined to write a Hardyesque novel. And by God I did — nearly 100,000 words this time and entitled, I deeply blush to remember, ROOTS IN THE MELLOW EARTH. By the age of nineteen, though, I just had to face up to it: I had not become a Beatle, I was not the everlasting love of Julie Christie's life, and now I had quite spectacularly failed to rival Thomas Hardy.

From The Independent

MEMORIES OF THE FLASK BOOKSHOP, HAMPSTEAD

Joseph Connolly outside the Flask Book Shop

I remember the distant days when Keith Fawkes's adjoining bookshops were a greengrocer and a chemist, respectively. And opposite those was a charming and tiny proper old sweetshop staffed by a couple of ladies who seemed to be about a hundred years old: they used to help each other in lifting down the great glass jars of aniseed balls, humbugs, mint lumps and gobstoppers. Before it became Pennifeather (known in the eighties, at the height of the yuppie boom, as 'The Filofax Shop') it was a jeweller — scene of a spectacular daylight armed robbery, when all my customers fled to the basement and I, rather stupidly, didn't. Then it became a branch of Rumbold's bakery — great sausage rolls and ham and cheese baps: I lived on them for years. Next door was Lodder's, a health shop whose best seller was full-strength Colombian coffee and gold- plated Cafetières — Ferns until recently, and now the purveyor of rather thrilling frilly things. The eternal fixtures of the street — never changing and strangely reassuring — are of course The Flask pub and J. Steele & Son, butcher (for you must have meat and drink). There was a Culpepper herbalist briefly, various optimistic galleries and a blank-windowed solicitor (never, though — thank God — an estate agent). And how could one ever forget Hampstead's answer to all the greats from Mister Teasy-Weasy to Nicky Clarke, by way of Vidal Sassoon, Kiki Continental, but naturally — the signwriter's dodge spacing always making it read KIKI CONTINENT AL (nothing to do with the great Alvarez though — who did and does live just down the road). They specialised, it seemed to me, in fluffing out and puffing up the thinning heads of elderly ladies and rendering the cottonwool result a fetching pink, or else a more subtle azure. And there was a jolly good art shop, which now sells fairies.

Joseph Connolly with Kingsley Amis

in Dunraven Street, Mayfair,

in 1988, on the occasion of the

unveiling of a blue plaque to P. G. Wodehouse

by H. M. The Queen Mother

There was a bookshop at number 6 since the 1950's, and maybe even from before the War — property of a certain Mr Fry. I bought the lease from the much-loved white-haired old couple Peggy and Jasper Waterhouse (brother and sister though — not husband and wife) who used to have a bookshop in the quaint and elegant Swiss Cottage Arcade, before it was swept away in favour of the horror that you see today (opposite the Odeon, and up a bit). The Flask Bookshop was marvellous, though — once I got it going again with first editions, art books, antiquarian and literature; on Saturdays, people would have to wait outside until there was room for them to squeeze in — this at a time when there were at least seven other bookshops in the Village alone. My best customers tended to be doctors, lawyers, actors (Peter O' Toole. Jeremy Irons, Peggy Ashcroft among many others — and once, after a bibulous lunch, the giggling trio of John Cleese, Michael Palin and Terry Gilliam) and happy clever penniless folk who just loved books (I didn't take credit cards — and often, I didn't take money either). Not many writers, though — Melvyn Bragg and John le Carré (separately) walked past the door three or four times a week, and in fourteen years never once walked in. Kingsley Amis did though — we had some jolly lunches at The Flask, and some jolly evenings too in his house down the road (Gardnor House — opposite what were still the public baths). And once, I cringingly recall, my five year-old daughter Victoria roundedly told off Michael Foot because his beloved dog Dizzy was making muddy footprints all over the floor.

By the mid-eighties, Hampstead had changed: only three bookshops left by then, but lots of video outlets and places to buy silk dresses. I was writing non- fiction books and a lot of freelance feature journalism, mainly for The Times and often had to turn down press trips, interviews and stories in order to man an increasingly lonely shop (I never could have afforded to pay anyone, for all that the rent was just £4000 a year: a struggle, though, every single quarter). I sold in 1988 in order to become a full-time writer and, I hoped, a novelist, which seems to have worked out.

And suddenly... oh goodness, it all just seems like yesterday. Isn't, though. Time passes, as if you didn't know it. But Hampstead in general — and Flask Walk in particular... don't they wear it well?